Sanna Erelä, Project Coordinator

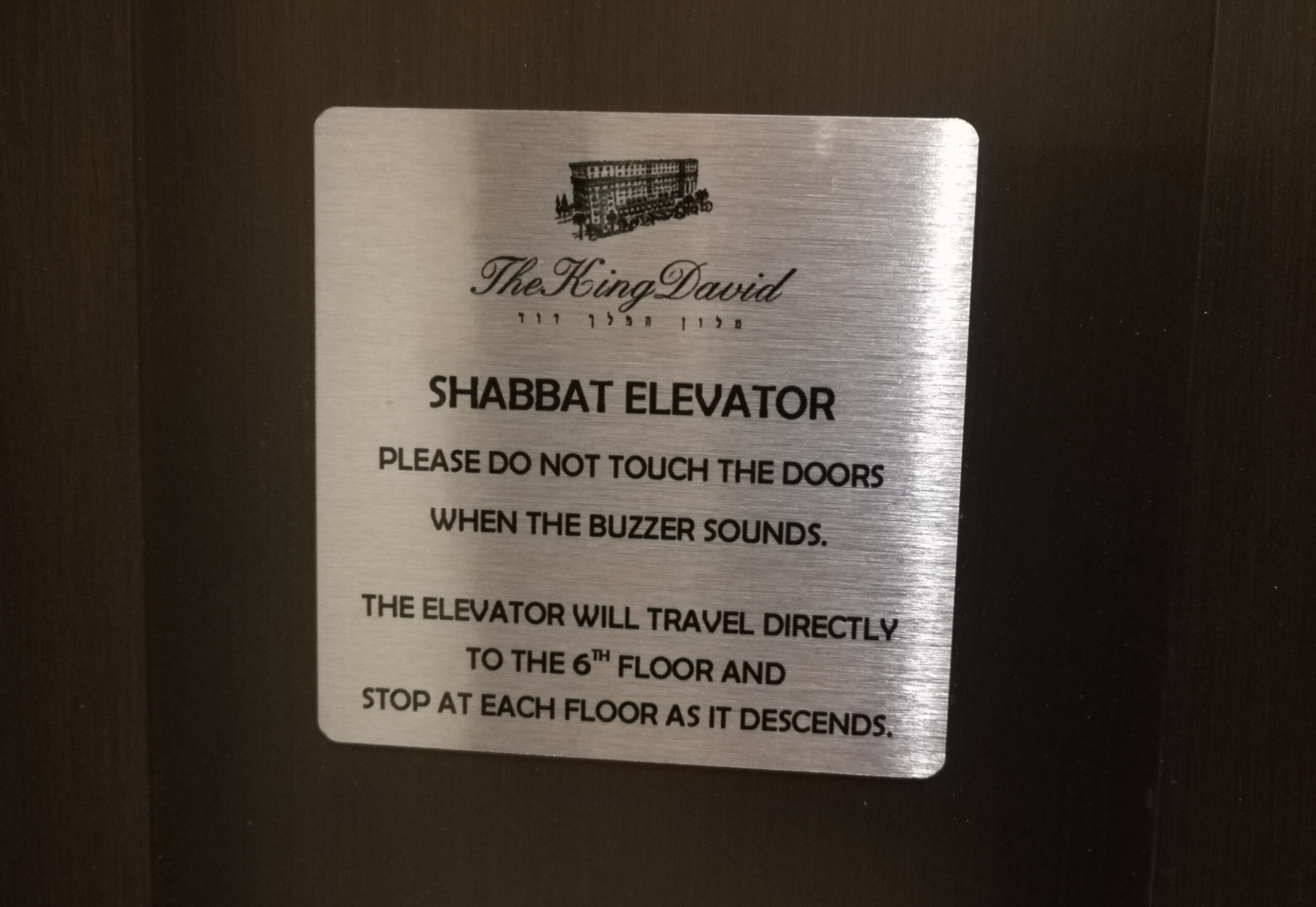

Shabbat is a special time here in Jerusalem. Most of my neighbors are religious Jews —not the black-wearing, isolated community members, but people whose daily lives are conducted by the Jewish tradition. As the sun goes down on Friday, and the Shabbat horn sounds over the city, a peace falls over the house. The entrance door is left unlocked, so that visitors do not need to press the buzzer. The energy-saving lamp lights the stairwell throughout the night. According to the Torah, fire-making is forbidden on Shabbat, and Rabbinic Judaism equates the use of electric switches with that. Therefore, religious Jews do not turn the power on or off during Shabbat. Timers and thermostats are needed, for example, to keep food warm. Many tourists staying in hotels in the Holy Land are familiar with the Shabbat elevators, which stop at every floor.

It seems that I am the only gentile in the house, because I’ll be approached when something goes wrong. The subtleties of the Jewish Law do not apply to people from other nations. Many times I have been asked to press the button for the air conditioner or radiator. The first time I must have looked quite stunned, but now I know what knocking on my door on Shabbat means. And if these little favors are the way to get in touch with my neighbors, I’m happy to go.

The Jewish Shabbat observance tends to make us Christians smile. The Jewish people represent to us the offspring of the New Testament Pharisees, and the Pharisees — so we believe — were hopeless hypocrites. We think that the present-day Jewish people are bound to the “letter of the Law”, and they are unable to see the difference between important and marginal issues. But in fact, we can’t afford to laugh. For me personally, all these years in Israel, Shabbat has been a lesson in rest and unwinding.

Israel is one of the world’s most active users of social media. On the bus, all under the age of 70 seem to have a mobile phone sprouting from their hand — that is, on six days of the week. On the seventh day, the phones are switched off, the internet is shut down, and the television is quieted. The Shabbat is a time for cool down and fellowship. The shops are closed, public transport stops. It is a time of sharing meals together, singing, going to synagogue (if the family is religious), and spending time with relatives and friends. What do you think: would you and your family be able to cut off all outside connections for one day on a weekly basis and just be together? For me that would be quite a challenge!

It was recently reported that excessive browsing on smartphones can cause impaired concentration and symptoms of ADHD, even in adults. It almost looks like the whole of Western society could be suffering from exhaustion and memory loss due to information overload. Overactive lifestyles and constantly beeping smart devices drive more sensitive individuals to puzzle, how they can cope with everything? And so, all kinds of downshifters, mindfulness teachers, and other alternative lifestyle gurus show up to rescue us. Is derailing to the other end really the only option for us? Where did the biblical idea of Shabbat go? Who would teach Christians to repose in “a mindfulness prayer”?

It was recently reported that excessive browsing on smartphones can cause impaired concentration and symptoms of ADHD, even in adults. It almost looks like the whole of Western society could be suffering from exhaustion and memory loss due to information overload. Overactive lifestyles and constantly beeping smart devices drive more sensitive individuals to puzzle, how they can cope with everything? And so, all kinds of downshifters, mindfulness teachers, and other alternative lifestyle gurus show up to rescue us. Is derailing to the other end really the only option for us? Where did the biblical idea of Shabbat go? Who would teach Christians to repose in “a mindfulness prayer”?

Once a year in Israel, on Yom Kippur, the Day of the Atonement, everything comes to a stop. On that day, a majority of the Jewish population fast from food, drink, and entertainment for 25 hours, to examine their hearts and repent from their sins. All traffic, from private cars to airplanes, stops. Even non-fasting Israelis respect the special character of the day. Although I, as a Christian, do not believe that fasting would cleanse anyone from sin, there is still something powerful in Yom Kippur. It is a picture of how our relationship with God should come first in our lives. It’s as if society itself is stopping to say: Without God we have nothing. Without him, we will not even survive.

The observance of the Jewish Shabbat may appear to Christians like a form of bondage. In the vaults of our minds, we hear biblical passages echoing that the observance of the Law is a distortion of the freedom of the Spirit. Indeed, for many Jewish women, the Shabbat rest doesn’t come for free. They need to do much preparation in advance so that the family can rest. Still, I wonder if we could learn something from them, without adding extra burden on ourselves or others? Should we Christians observe more discipline and order in our freedom, to give our overwhelmed brains a short break — not to mention the refreshing of the spirit and soul?

I don’t have a family of my own, so sometimes my Saturdays here are quite stagnant. There is no public transport, which limits meeting people and the way of spending the weekend. Over the years, I have learned to take this as a blessing — this Shabbat rest, whether I want it or not. Disconnecting from activities leads to silence, which at best is full of peace filled with the presence of God. Or not — sometimes it’s just extremely boring. In any case, my overly stimulated nervous system can recover.

The day of rest was determined for man already in creation. We have not changed since then, even though many shops in Europe are open on Sundays. The Jewish Shabbat teaches us the art of being present. Without smart devices and other continuous entertainment, we will have to come down from our imaginary worlds into this moment, into our own body. It can be liberating or boring, even painful, but it is in any case something that is true. God can also be met where we anchor ourselves to reality. Jesus, the Lord of Shabbat may speak to us, when we are present for ourselves and others.